As space enthusiasts, we're accustomed to "thinking big." We know that the sun is roughly a hundred times the size of the earth, so that roughly a million earths would fit inside the sun. We know that the earth is about 93,000,000 miles from the sun. We know that a light-year is almost 5.9 trillion miles, and that our own galaxy is about 160,000 light-years across, containing more than 100 billion stars; and we know that there are billions of galaxies in the universe.

But what about things "nearer to home"? (No, I'm not talking about money here.) After one or two of my customary digressions, I will address the question: Do we always think big? Do we think big enough?

When I was in second grade, I was given one of the books that helped spark my interest in science. It was How Big is Big? and was a sort of precursor to the original "powers of 10" video that came maybe ten years later. To be perfectly honest, I still have it (shown here).

I promise this entire post isn't about chilhood reminiscences (or even about "orders of magnitude" as such). Please bear with me.

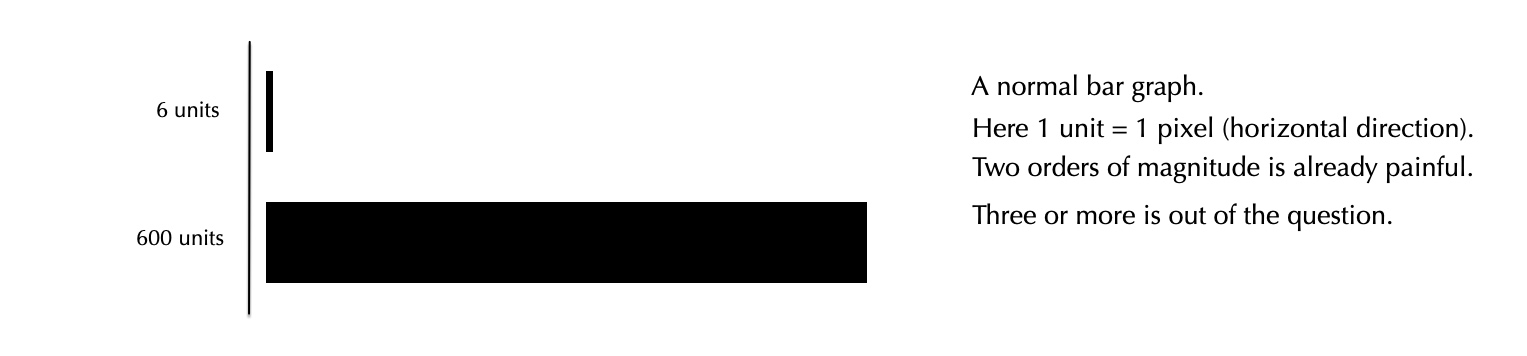

Since I'm talking about relative sizes here, a graph seems appropriate, and a bar graph seems obvious. But I quickly realized that a bar graph is not very suitable for "orders of magnitude" differences. For example, consider these two bars that differ by only two orders of magnitude (a factor of 100).

Obviously it's impractical to use such a bar graph for numbers whose sizes differ significanty. I considered some kind of logarithmic graph, but that seemed to defeat the purpose. It didn't seem intuitive enough.

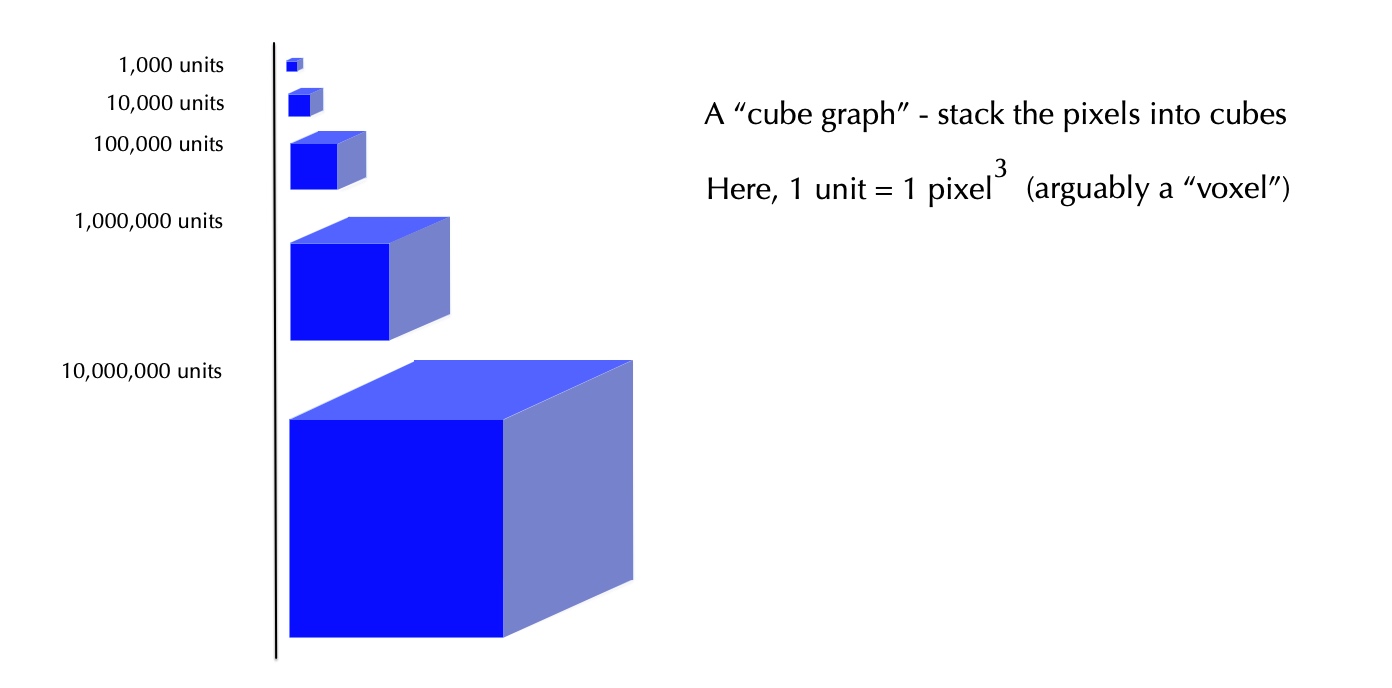

I settled on the idea of a "cube graph," where the width of the figure is essentially the cube root of the quantity being graphed. (I am certain I did not invent this, although a quick web search didn't reveal anything obvious.) Here is an example.

|

So, armed with this visual technique, let me address the real point of

this little essay. The numbers I am talking about are the memberships of

the various space groups. In a few paragraphs, I'll compare them with

some other segments of the population (non-space related).

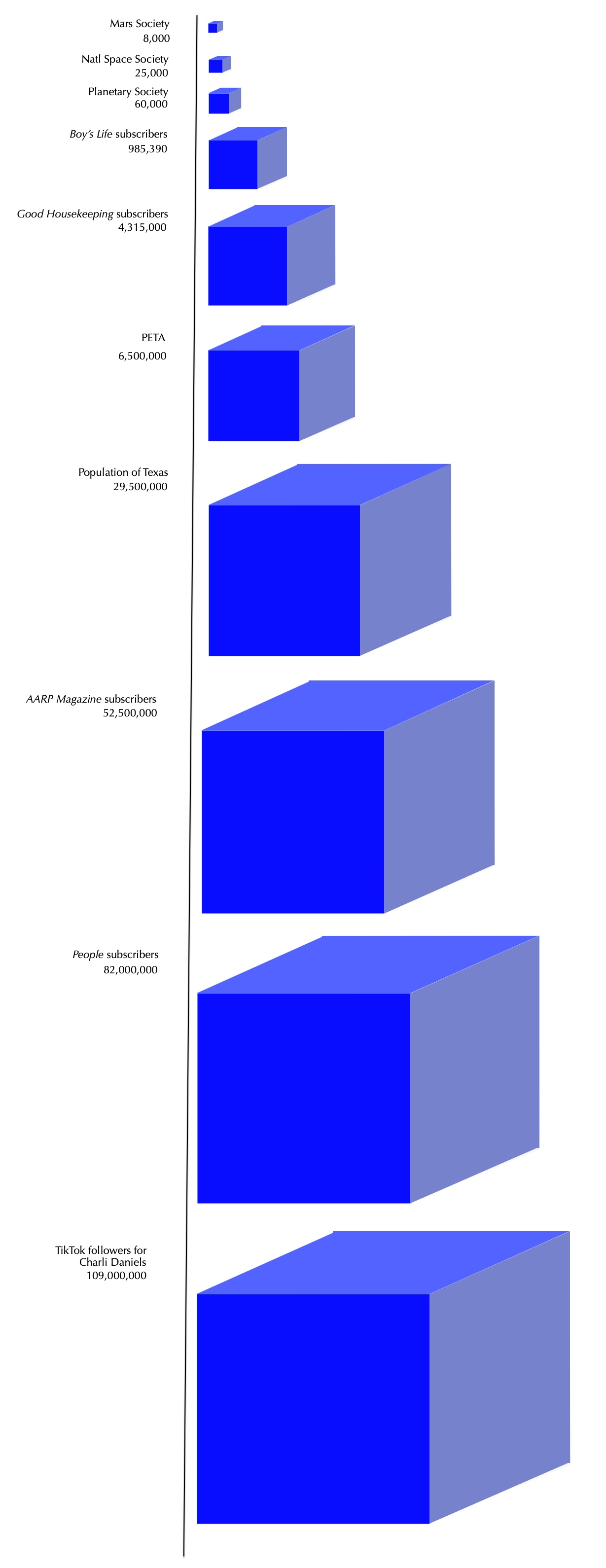

In the space community, the NSS is one of the biggest fish in the pond. But how big is that pond really? As I've said, the boundaries of the space community are fuzzy, vague. But let's look at some of the largest nonprofits (using numbers that are probably out of date). Sources on the web disagree, but let's assume 60,000 members for the Planetary Society; 25,000 for the NSS; and 8,000 for the Mars Society. So far, we are barely in the neighborhood of 100,000 individuals. Let's be a little generous and say the space nonprofits total 150,000 people. That is less than the number of subscribers to Cat Fancy magazine before it ceased publication. The Michigan Stadium (capacity 107,601) would hold more than two thirds of these people. The entire membership of all the space nonprofits could visit Indianapolis Motor Speedway (and only be at 60% capacity). So here is a graph comparing space groups to some other groups. Be sure to stick around for my final paragraph, where I will express my strongest opinion. I'll allow you to do the arithmetic yourself, but I'll throw in just a few observations. The Boy's Life subscribers outnumber the NSS nearly 40 to 1. The PETA volunteers outnumber the Planetary Society by more than 100 to 1. As for the state of Texas— well, I just added that for fun. Not only does Texas dwarf the entire space community by perhaps 200 to 1; but there are influencers on TikTok and Instagram that outweigh Texas or any other state. There are teenagers on social media whose following is far larger than the population of many of the world's nations. A natural question is: Why do some organizations or causes attract people in the tens of millions while others attract only thousands? There are many possible answers. It's possible to be cynical and say that most of the masses are ignorant and short-sighted, interested only in mundane, frivolous, mindless entertainment. While there may be some truth there, I prefer not to be that cynical. What if we say that people tend to be ignorant of certain topics? That is getting nearer the truth, but there is still more. I argue that people care more about a cause when it is immediate and relevant. Space, to most of us, is anything but immediate; and it is anything but relevant. While I was writing this post in May 2023, I ran across the excellent article "Breaking out of the space echo chamber" (Bob Werb on spacenews.com). If you have the patience to read my writing this far, I urge you to read this well-written piece as well. Why isn't there a space group anywhere with 100,000 members? We have to reach 100,000 before we reach 1,000,000 or 10,000,000. Are we thinking big enough? Let me summarize this topic by painting with a very broad brush. One party (the space community) is sending an important message (that space is worthwhile) to another party (the general public). The message is not being received or is being ignored. What went wrong? Is there "something wrong" with the message? Of course, I argue there is not. Is there some fatal defect in the people sending the message? Or in the people receiving it? Again, I claim there is not. Humans being humans, there are always some who think or behave in ways that are incorrect, uncharitable, or unproductive. But let's give both the sender and receiver the benefit of the doubt. Where is the problem, then? I maintain that the problem is in the transmission of the message. And yes, that does imply in a way that there is a sort of problem with the senders. As cartoonist Walt Kelly said, "We have met the enemy, and he is us." I have many thoughts on this topic which I will share later. Some may prove to be totally useless, but I hope some may resonate with others and lead to greater understanding here and there. On the average, we in the space community are not great communicators. There are, of course, numerous counter-examples! But overall... we can do better. The problem is not in the message or in the people hearing it. The problem is one of communication. We as a whole need to communicate differently and better.

|

|